THE WAY OF THE CROSS

Jerusalem

Margaret Deefholts

For Travel Writers' Tales

Camel reposing at the Mount of Olives lookout over Old Jerusalem

We are standing at a lookout point on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, and our guide, Carmela, with a theatrical sweep of her hand, announces, “Folks, I give you the Old City of Jerusalem!” A wag among our group says, “Really? You sure you don't want it any more?”

The old walled city of Jerusalem

and the glittering Dome of the Rock

In the heat shimmer of this June afternoon, the buildings within the crenelated city wall, are a jumble of toy-sized blocks and although historic Jerusalem is divided into four quarters – Jewish, Muslim, Christian and Armenian—it is impossible to distinguish any boundaries. From our high vantage point, the golden Dome of the Rock shrine on Temple Mount, glitters in the sun.

“For Muslims, the sacred Rock within the building marks the place where the Prophet ascended into heaven accompanied by the angel Gabriel” says Carmela, “and according to our Jewish tradition, this Foundation Stone is also where Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son Isaac.” Directly below us is the vast and oldest Jewish cemetery in the world.

Jerusalem is also at the core of Judeo-Christian tradition and, standing here looking at the Holy City, I find myself shedding adult scepticism and being drawn back into childhood's simplicity of faith.

Basilica of the Agony in Gethsemane

Old Jerusalem

Below our lookout and partly hidden by trees is the tear-shaped Dominus Flevit (“The Lord Has Wept”) where Jesus cried as he visualized the destruction of Jerusalem. Here too is the Basilica of Agony where He once prayed: “O my Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me.” He was a sorrowful human being then, not the transcendent “Christ” figure he would later become. In resigned acceptance he then says, “Thy will, not mine, be done…” A little further down the hill is the Chapel of Gethsemane marking the scene of Judas' kiss of betrayal.

View of Hagia-Sion Benedictine Abbey

Old City of Jerusalem

We drive to Old Jerusalem dismounting near the sturdy walls of the Hagia Sion, a Byzantine Abbey.

The Western Wall, (commonly referred to as the Wailing Wall) is the only surviving relic of the Second Temple of the Jews, built by Herod and later destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD. It is where Jews traditionally congregate to mourn the loss of their Temple – a symbol of ancient worship and solidarity. Today being Sabbath, the square is deemed to be an al-fresco synagogue – a place of solemn worship, and (to my disappointment) no photography is permitted.

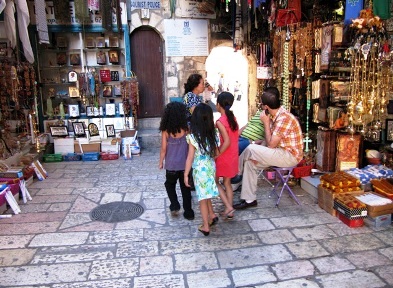

Shop keeper on a street in Old Jerusalem

Families throng the plaza: men wearing yarmulkes, white shirts and black coats. Some have Hasidic ringlets, bowler hats and tzitzits (tunics with white tassels); women wear scarves and long sleeved dresses. Despite the loss of their ancient Temple, there is confidence in their bearing – for the Wall is now as much a symbol of lost yesterdays as it is a promise of tomorrow. It epitomizes freedom to worship in this historic land bequeathed to the children of Israel by Jehovah. It is gratifying to watch these men and women who have reclaimed their proud heritage after centuries of struggle. Yet, for all that, there is also something disturbing about the implacable intensity of their gaze—stern, unyielding.

I join the line to the women's area (separated from the men by a screen) and lean my head against the ancient grey stone, feeling the rough surface against the skin of my forehead. The emotion around me is as palpable: an elderly woman next to me rocks back and forth in profound prayer and beyond her a young girl holds a prayer book to her forehead, murmuring softly. Both are oblivious to everything around them.

The sun is hot against the nape of my neck. I close my eyes, trying to isolate and hold this moment – mysterious, and as precious as any experience in a cathedral or Buddhist temple. I place a small piece of paper with a prayer of thanksgiving to Jehovah into one of the cracks between the stones.

View of the symbolic bronze fig tree in the Upper Room:

Scene of the Last Supper

Back on the Christian trail, we visit the “upper room” where Jesus and his disciples celebrated their last Passover meal together. Located over the ancient tomb of King David, this room, built at the time of the Crusaders in the 12 th century has replaced the original chamber. It is almost stark in its simplicity: a Gothic vaulted ceiling, stairs leading to an inner room, a carved marble niche, and a symbolic bronze olive tree on a raised platform. It is here that Jesus instituted what endures as the most reverential of all Christian rituals—the offering of bread and wine as a symbol of His body and blood, sacrificed to redeem the world.

Children at the entrance to the Via Dolorosa

Religious souvenir shop along the

Via Dolorosa

The Via Dolorosa—the “Way of Sorrows” is a narrow cobbled street. Even in biblical times it was, just as it is today, a thriving market place. It is a swirl of movement and colour: tourists and touts, and the whole sad spill of tawdry religious debris—stained-glass images of the Virgin and the Last Supper, vials of holy water, crucifixes, rosaries. A group of nuns flutter past like a flock of white doves, a couple of bearded Jews with long sideburns edge by me, and a hawk-nosed old man with smouldering eyes sits unsmiling in front of his souvenir shop.

Entrance to the Via Dolorosa - Jerusalem

Via Dolorosa - Old City

Yet in the midst of this seething commercialism, suddenly for me—not a particularly devout Anglican—the story of this tragic Man of Sorrows takes on reality. I see him, scourged, crowned with thorns, staggering up the hill to Golgotha, thin and emaciated, his face streaked with blood and sweat, his back striped with welts while carrying the cross—a heavy wooden implement to which he would be nailed to die. I am impelled to place my hand in the alleged imprint of Christ's hand in the rock—worn smooth now by others before me—and to lean against the rock where he would have stood as Simon of Cyrene helped him to carry the cross.

Author at the Station of the Cross marking the spot where Jesus fell and then rested his hand on the wall as Simon of Cyrene helped him to carry the cross.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is unpretentious when compared to the grandeur of St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican, but it is unequivocally the most emotionally moving site in all Christendom.

Pilgrim praying in the courtyard of the Church

of the Holy Sepulchure - Jerusalem

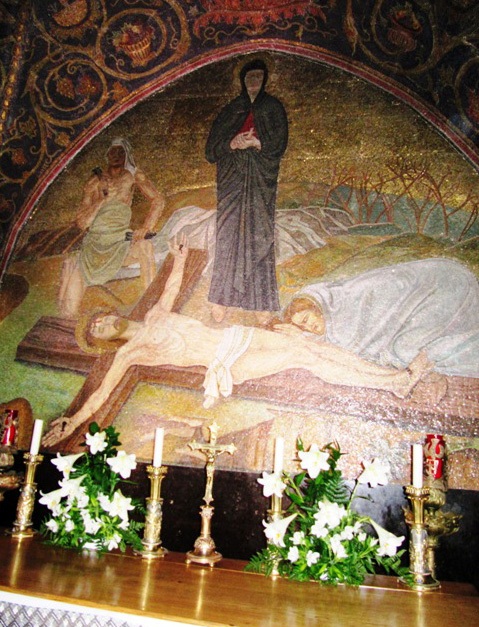

Painting in the Chapel of Mary - Church of the Holy Sepulchure

I climb the spiral stone staircase leading to the chapel of the Rock of Calvary. A glittering altar covers the actual spot where the crucifixion took place, and a woman kneels to touch the sacred Rock through a small aperture at the base of the altar. She rises and wipes her eyes she turns to leave.

Altar with window built over Golgotha - Site of the Crucifixion

Church of the Holy Sepulchure, Jerusalem

Woman praying at Golgotha Window

To the left of the main entrance, is the Rotunda, and leading off this is a small entrance into the holiest of shrines—the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre containing Jesus' tomb and a marble slab which marks the spot where the risen Christ emerged triumphantly three days after he was crucified. The line up of pilgrims, many with their eyes closed in prayer as they wait to enter the doorway, is to witness faith at its most awe-inspiring.

Mural - Church of the Holy Sepulchure

Entrance to the Tomb of Jesus: Church of the Holy Sepulchure

The life and death of Jesus of Nazareth is indisputably the most revered as well as the most controversial story of all time. For every cynic who calls it a tale of “cruci-fiction”, there are millions more who are deeply moved by the terrible yet humbling drama they believe took place here in the heart of Jerusalem more than 2000 years ago—an event which changed the course of Western civilization forever.

________________

Travel Writers' Tales is an independent travel article syndicate that offers professionally written travel articles to newspaper editors and publishers. To check out more, visit www.travelwriterstales.com

IF YOU GO:

For information contact the Israel Tourism Office, Toronto: https://info.goisrael.com/en/canada

Web: www.goisrael.ca

Other Purported Site of the Crucifixion:

http://www.sacred-destinations.com/israel/jerusalem-garden-tomb

Where to Stay: The Leonardo chain of hotels offers luxury at reasonable rates. See http://www.leonardo-hotels.com/hotel-contacts

PHOTOS: Margaret Deefholts