Page 5

MURDER, MAYHEM AND MYSTERY ON THE CARIBOO GOLD RUSH TRAIL

We are now on our final stretch to Barkerville. It is late afternoon and the sky has turned sullen. By the time we dismount in the parking lot, a cold malicious drizzle whips against our faces. Most visitors have gone home, and we make our way to the Lung Duck Tong restaurant in the Chinatown sector. The building dates back to the early 1900s and the hospitality, like the food, is generous. Piping hot too!

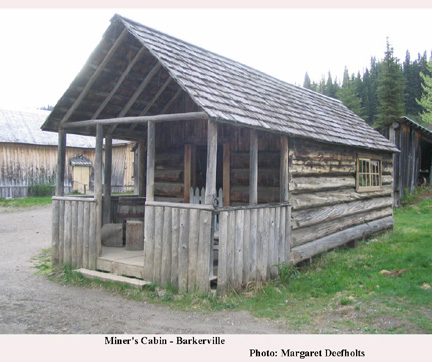

Barkerville is where illusion and reality merge. The rain has disappeared by morning, and the main street buzzes with activity. At the door of the school house, Miss Mary Hastie stands primly awaiting the arrival of her pupils, and further up the road, a whiskered gentleman in a top hat and cape bows a polite, “Good morning Ma'am” to a pretty young woman dressed in a crinoline. A couple of kids emerge from the costume shop: the little girl wears a bonnet and pinafore; her older brother is in a waistcoat, necktie and burglar cap. Mum and Dad are also in period costumes, and the family beam as an obliging miner puts down his shovel and clicks a shot before handing the camera back to Dad. Visitors peer into the windows of log cabins; some stop to watch Mr. Cameron at work in the blacksmith's shop, while others buy candy and postcards at the Mason & Daly General Store. A group of school kids, also wearing Victorian costumes, whoop and wave as their stage-coach rumbles past me.

Barkerville is where illusion and reality merge. The rain has disappeared by morning, and the main street buzzes with activity. At the door of the school house, Miss Mary Hastie stands primly awaiting the arrival of her pupils, and further up the road, a whiskered gentleman in a top hat and cape bows a polite, “Good morning Ma'am” to a pretty young woman dressed in a crinoline. A couple of kids emerge from the costume shop: the little girl wears a bonnet and pinafore; her older brother is in a waistcoat, necktie and burglar cap. Mum and Dad are also in period costumes, and the family beam as an obliging miner puts down his shovel and clicks a shot before handing the camera back to Dad. Visitors peer into the windows of log cabins; some stop to watch Mr. Cameron at work in the blacksmith's shop, while others buy candy and postcards at the Mason & Daly General Store. A group of school kids, also wearing Victorian costumes, whoop and wave as their stage-coach rumbles past me.

I'm just in time at the Visitors Reception Centre to join Mr. Joshua Thompson and the saucy Miss  Rebecca Gibbs as they conduct a group through historic Barkerville. The lady informs us that not only is she the town's best laundress, but she is also a poet of considerable talent, who Mr. Thompson, as the owner of the Cariboo Sentinel, is privileged to have as a frequent contributor to his newspaper. Mr. Thompson raises his eyebrows at this, but knows better than to comment.

Rebecca Gibbs as they conduct a group through historic Barkerville. The lady informs us that not only is she the town's best laundress, but she is also a poet of considerable talent, who Mr. Thompson, as the owner of the Cariboo Sentinel, is privileged to have as a frequent contributor to his newspaper. Mr. Thompson raises his eyebrows at this, but knows better than to comment.

Mr. Thompson leads us along the main street and points out the Tregillus home. Fred Tregillus, who owned the longest mining licence in British Columbia , lived here from1886 till his death just a few months shy of his 100th birthday in 1962. A little further along the boardwalk a spanking white house, with curlicued gables, was the home of John Bowron, Barkerville's Gold Commissioner, Town Librarian, and Postmaster.

Across the street is an original pre-1900s house, occupied by John's son William Bowron. His business partner, Joe Wendle, lives next door, and I peek into the kitchen where Joe's sister and housekeeper, Julia Wendle, is preparing a special pudding as a celebratory treat. “Joe came home with wonderful news last evening,” Julia tells us, her eyes dancing. “They've hit a lode at the Hard Up claim, and it looks like a bonanza! About time too—its been two years of bitter disappointment up to now.” She urges us to come back and sample her dessert later that afternoon.

It is here in Barkerville that I finally meet the formidable Judge Begbie. He is striding down the street on his way to hold Assizes court at the Wesleyan church hall. “Will James Barry be in the prisoner's dock?” I ask. He shakes his head. “No, Ma'am, not today. But if you wish you may attend the Richfield courthouse in July,” he says. “That's where I will be passing sentence on Mr. Barry.”

The story leading up to the sensational trial, was an unusual one. In May of 1866, Charles Morgan Blessing and a companion, Wellington Delaney Moses, were on their way to Barkerville when they met up with James Barry at Quesnellemouth. Barry persuaded Blessing to join him on a side trip, while Moses continued on to Barkerville where he opened a barbershop. Several weeks later Barry showed up in Barkerville alone, claiming to have no knowledge of what had happened to Blessing.

Moses distrusted Barry's evasive manner from the outset, and his misgivings grew stronger when—as the tale goes—shortly after Barry's arrival, Charles Blessing walked into the barbershop one morning indicating that he needed a shave. Moses was relieved to see him but was, nonetheless, shocked at Blessing's appearance—his clothes were torn and filthy and his eyes were hollow. The barber sharpened his razorblade, but when he turned around, he was aghast to find that the moist towel he'd used to covered his friend's face was soaked in blood. He'd no sooner let out a cry of alarm, when the apparition vanished. This all but convinced Moses that Blessing had been murdered, and his suspicions were confirmed when a Hurdy-Gurdy dancer showed him a distinctive gold tie-pin in the shape of a skull given to her by Barry. Moses recognized it instantly. Meanwhile Blessing's corpse, with a bullet hole through its skull, had been discovered in the bush. Witnesses testified to the fact that Barry was armed with a pistol, but the definitive piece of evidence was Blessing's gold tie-pin.

With the hindsight of time, I know the outcome of the James Barry case. To quote Judge Begbie as he pronounced sentence on Barry: “You have dyed your hands in blood, and must suffer the same fate. My painful duty now is to pass the last sentence of the law on you, which is that you be taken to the place of execution, there to be hanged by the neck until you are dead; and may the Lord have mercy on your soul.”

With the hindsight of time, I know the outcome of the James Barry case. To quote Judge Begbie as he pronounced sentence on Barry: “You have dyed your hands in blood, and must suffer the same fate. My painful duty now is to pass the last sentence of the law on you, which is that you be taken to the place of execution, there to be hanged by the neck until you are dead; and may the Lord have mercy on your soul.”

I am not sure whether Blessing's ghost still stalks the streets of Barkerville, but the town plays host to several other spectral inhabitants. Certainly everyone I chat to on the subject seems to have a favourite yarn to spin. Although no one has been able to identify him, a man in top hat and tails has been known to materialize briefly, on stage left at the Theatre Royal. A shadowy woman at an upstairs window of the old Barkerville Hotel (now converted to a heritage museum and gift shop), has been sighted on several occasions, even though the building is empty and locked up at the time. The St. George Hotel , too, has a mysterious phantom, a young blonde woman dressed in white, who appears around midnight by the bedside of lone male visitors. Women guests, it would seem, aren't worth her wile!

Some of Barkerville's ghosts are prankish poltergeists, others are solitary and wistful. None of them appear to be evil or violent. Perhaps this is because Barkerville's past contains few heinous criminals. Other than Barry's hanging, the only other execution that took place here, was that of a native Indian found guilty of murdering a man at Soda Creek. The town, then known as Williams Creek, had none of the rambunctious lawlessness of other American gold rush frontier towns, and while it had its share of gambling dens and sporting houses in the Chinese quarter, its saloons, dance halls, and rooming houses operated discreetly and—as in the case of a bordello run by the colourful Madam Fanny Bendixon—even with some measure of style. A few saloons offered entertainment by German or Dutch Hurdy-Gurdy dancers, and although some of them were women of easy virtue, others were from respectable, if impoverished backgrounds. Many of them married into Barkerville families and settled down in the Cariboo. Today, at the Theatre Royal, where I peer nervously at the shadows lurking in the stage wings, an amply endowed Hurdy-Gurdy dancer dressed in a traditional red dress, recounts her life in Williams Creek . The audience chuckles loudly at her double-entendres, and applauds enthusiastically at the end of her show. The racket is enough to discourage any self-respecting spook.

Barkerville's most famous character is its namesake, Billy Barker. Yet Barker would never have come anywhere near the area, if it wasn't for Dutch "Bill" Dietz, one of the first prospectors to discover flecks of gold dust in the waters of Williams Creek (named after him) which resulted in a frenzied of rush of prospectors in 1861—among them the choleric 44 year-old Billy Barker. Apocryphal tales about Mr. Barker abound, but a favourite among them is that he was haunted by a recurring dream in which the number 52 seemed to carry a mysterious significance. Bearing out the tale is a laconic marker along Barkerville's main street recording the spot where, according to legend, Billy Barker on August 17th 1862 hit pay dirt at a depth of 52 feet! Billy Barker realized half a million dollars in today's currency, but squandered it all in abortive mining ventures, to die penniless at the age of 77. He is reputedly buried in an unmarked pauper's grave in Victoria 's Ross Cemetery .